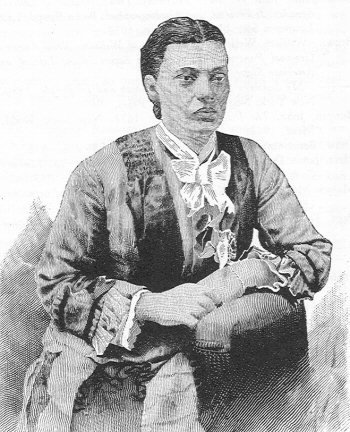

The full title of Octavia Albert’s narrative tell a story in itself: The House of Bondage, or, Charlotte Brooks and Other slaves, Original and life like, As they Appeared in Their Old Plantation and City slave life; Together with Pen-Pictures of The Peculiar Institution, with Sights and Insights into Their New Relations as Freedmen, Freemen and Citizens (1890) Albert’s title, like many other titles of narratives (almost as long as the narratives themselves!) suggest the real human drama that was slavery–the arbitrariness of life, the chaos, the fear— all of which mirrored to some extent what was taking place in the continent they left behind….

Mrs Albert, who was born a slave but was a child at the time of Emancipation, grew up to be a teacher in rural Georgia who eventually married a preacher. It was in their home that she began to take in older ex-slaves and eventually recorded their stories. So we have that rarest of circumstances — an ex slave who becomes an interpreter of her own experience and the experience of others…..

She begins her book with a strong voice that establishes her authority on the subject: “None but those who resided in the South during the time of slavery can realize the terrible punishments that were visited upon the slaves. Virtue and self respect were denied them…”

With such an introduction, she goes on to detail some of those cruelties suffered by the likes of Charlotte Brooks and other slaves. Lest there be any who would whitewash the evils of slavery, as was already being done so few years after Emancipation, she quotes Brooks as saying:

“Why, old marster used to make me go out before day, in high grass and heavy dews, and I caught cold. I lost all of my health. I tell you, nobody knows the trouble I have seen. I have been sold three times. I had a little baby when my second marster sold me, and my last old marster would make me leave my child before day to go to the cane -field; and he would not allow me to come back till ten o’ clock in the morning to nurse my child. When I did go I could hear my poor child crying before I got to it. And la, me! my poor child would be so hungry when I’d get to it! Sometimes I would have to walk more than a mile to get to my child, and when I did get there, I would be so tired I’d fall asleep while my baby was sucking.”

..It is no wonder that many slaves turned to the world of the spirit to understand and to exercise some authority, if only moral authority, in their powerless worlds. Hence the plethora of religious references in this book and many other slave narratives. Religion was not some esoteric spiritual experience, it was an opportunity to transcend and overcome present-day circumstances. Some had a genuine encounter with what some may call today liberation theology. Thus worshipping their God in their way was a major act of defiance. After one of the several hymns referenced in the narrative, Aunt Charlotte says: “Yes, my dear child, that hymn filled me with joy many a time when I would be in prison on Sunday. I’d sit all day singing and praying, I tell you, Jesus did come and bless me in there. I was sorry for marster. I wanted to tell him sometimes about how sweet Jesus was to my soul; bu the did not care for nothing in this world but getting rich.”

…Again, to her mind, she had something that those with all the power and the money could never have— not as long as they participated in her oppression. This was resistance of a very high order.

Excerpt from the chapter, “Subversion of the Sacred,” African Voices of the Atlantic Slave Trade: Beyond the Silence and the Shame, Anne C. Bailey (Beacon Press, 2005)

Picture By Unknown – http://www.blackpast.com/?q=aah/albert-octavia-victoria-rogers-1853-1890, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10595836

Find Anne C. Bailey's non-fiction book :

Find Anne C. Bailey's non-fiction book :