Charleston. Charlottesville. Pittsburgh.

NO! This cannot be happening again. We can not be silent.

We are grieving but we will not be silent.

On June 17, 2015, Dylann Roof, a twenty one year old white supremacist murdered nine African Americans who were attending a prayer service at the historic Emmanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, SC. Yesterday, October 27, 2018, eleven Jews were gunned down at the historic synagogue,Tree of Life, in the community of Squirrel Hill, Pittsburgh, Pa. “Tree of Life is a part of our beating heart. It is a part of our soul,” said Joel Rubin, former Deputy Assistant Secretary of State and member of the community.

The truth is right now, it is a part of all of our hearts, all of our souls.

This is not about politics. This is about human life and an appreciation of all lives…equally. This is about words and how much they matter.

A War of Words

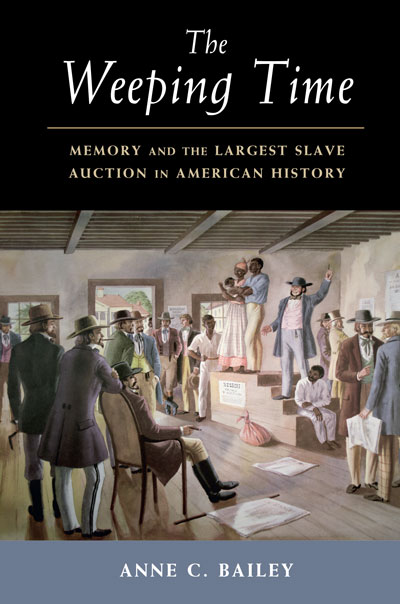

In my book, The Weeping Time, I wrote about what preceded the Civil War and the 620,000 lives that were lost in that tumultuous war:

The South may have started the war, but it could be said that war was brewing between the North and the South for many years prior. Though both were economically dependent on the other, there were great tensions pertaining to the question of the extension of slavery into new territories such as Kansas and Nebraska. The difference in each region’s economies also contributed to the conflict. The South with its four million slaves was largely agrarian whereas the North was a center for highly industrialized factories. Ironically, these same factories depended on the raw materials harvested by slaves such as cotton and tobacco for their operation. Both regions also differed in character. The Southern Gentleman, for example, saw himself as associated with the older notions of European nobility. He was the lord of his manor, and those four million slaves were expected to be loyal vassals who served him at will.[i]

In defending slavery, they were not simply defending the institution itself, but their manhood.[ii] Before the war, this defense took place in a war of words. “Through bloodless conquests of the pen, ….” they hoped to “surpass in grandeur and extent the triumphs of war.” [iii] They saw themselves as responding to the attacks of William Lloyd Garrison’s newspaper The Liberator that he established in the 1830’s. They were also responding to attacks on the ground from Nat Turner in the Virginia slave revolt in 1831 and later John Brown in 1859. The editor of The Southern Review, John Underwood, declared defiantly: Northern assailants should be met and “never suffered to enter the citadel till they walk over our prostrate bodies.” [iv]

It was a war of words at first but also a war between two ideologies. Many Southerners like Calhoun did not believe that all men had a right to liberty and rejected Jefferson’s claims of inalienable rights.[v] They could not accept the notion that black people could be accepted as free persons into the national fabric of American life. Such a fundamental conflict ultimately was not resolved in words but in war with the South striking the first blow but finding themselves eventually outmanned and outresourced by Northern forces.

Freedom is not license

So the war started first with words. Yet if there is one thing that distinguishes America from so many countries around the world is the principle of freedom of speech enshrined in The Constitution. Freedom, however, is not license. It is not license to say anything you want. If I cry, “Fire!” in a crowded theater and that causes a needless stampede, I should be liable for such speech. I may be free to say something, but also have to consider the consequence of my speech. Furthermore, in order to preserve this much treasured freedom of speech, I MUST consider that freedom is not license. I must choose my words very carefully. And that means all of us, not just our leaders, though especially our leaders, but also the rest of us. We are all responsible for our words which may, intended or not, lead to unforeseen and regrettable actions. That said, even within these boundaries of self -restraint, I do not have to agree with the speech of others. I can disagree, agreeably. That ultimately is freedom of speech at its best: freedom to disagree agreeably. It’s the little but important thing keeping our democracy together.

Yes, words matter. We have to consider our words.

I leave off today with these words: Words of deepest condolences for the families of those who lost their lives today; words of praise for the Pittsburgh police officers who prevented an even greater carnage from taking place. And finally, words from Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the German Christian minister who along with a small group of dissenters spoke out against Hitler and his xenophobic words and actions. He and others formed the Confessing Church and gave his life dying for his beliefs.

He famously said what could be called a rallying cry for the importance of words:

“Silence in the face of evil is itself evil: God will not hold us guiltless. Not to speak is to speak. Not to act is to act.”

Anne C. Bailey

Author of The Weeping Time: Memory and the Largest Slave Auction in American History. (Cambridge University Press, 2017)

[i] John Hope Franklin, The Militant Souhttps://www.amazon.com/Weeping-Time-Largest-Auction-American/dp/1316643484th 1800-1861, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1956) p?

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Ibid., p. 81

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid, 82.

Photo courtesy of Artem Bali, Unsplash photos

REVIEW: Pondering the First Purge by Monet Schultz, BU Class of 2018

The First Purge, a film directed by Gerard McMurrary and written by James Demonaco, stars Y’lan Noel, Lex Scott Davis, Jovian Wade, and other notable actors. This prequel thriller debuts five years after the initial Purge film was released. By the end of this film, I found myself contemplating if the hypervisibility of black death and the violence that follows was an indication of the intensity necessary to combat state sanctioned violence.

The film is set in Staten Island, during a time of nationwide instability, influenced by racial and economic unrest. The idea of purging is thought to be a “sociological experiment” created by Dr. Updale, a psychologist that believes that if citizens released their volatility, society will become peaceful. Under the new administration, the New Founding Fathers of America, a 12 hour period of lawlessness is enacted.

When I initially saw the extended trailer for The First Purge, I thought to myself “here we go again.” The sporadic visual of a protagonist Nya (played by Lex Scott Davis), as she stood on a jeep screaming and protesting “DO NOT PURGE,” was all too familiar. The screen felt like the walls were closing in and we were moments away from this dystopian depiction becoming a reality. I knew that Davis’ character was protesting purging because she knew that the only folks that would suffer from the sadistic game of middle-aged white politicians would be poor black and brown people.

“Our neighborhood is under siege from a government that doesn’t give a sh*t about us” rang in my ear, as Dmitri (played by Y’lan Noel) the neighborhood leader/drug dealer/gangster/hero proclaimed to his soldiers on the night of the Purge. I knew where this was going. I was going to watch another movie that illuminated America’s negrophilic inclination. That is the way negrophilia works. In the 1920s-30’s when negrophilia looked like nothing short of an obsession of jazz, African art, dancing the Charleston, mass media at the same time propelled the nauseating state violence that accompanied this phenomenon. To me, it looked like Hollywood was capitalizing off of the current real-life fears and reality of Black American life.

“Let’s create a political-horror movie that will scare the crap out of some, and will desensitize the rest” must have been the line of thinking in creating this film, right? Maybe. I’d have to watch the film and see. But then I thought to myself, given all you know, is this political horror film not plausible? Is it not a very real possibility? Most would hope not.

So I watched the movie. I was surprised, not disappointed. I was surprised at the not-so-subtle call for reactive violence, which was a common theme throughout the movie. Without giving away any spoilers, I will try to describe what that means. After protests fell on deaf ears and the Purge commences, the marginalized communities decide to have a massive block party. This was surprising because it shows that people, especially people of color are not inherently evil; this was not the direction I thought the film was heading. Shortly after, the government unleashes mercenaries to incite violence during the block party. Ultimately, marginalized groups in Staten Island come together to do their best to protect themselves by fighting back.

What The First Purge had me pondering was if the fixation and hypervisibility of Black death will ever make black people free? Will The First Purge’s theory of fighting back make black people free? And fighting back doesn’t necessarily mean fighting back violently, but it does mean some struggle must take place. In the words of Assata Shakur, “No one is going to give you the education you need to overthrow them. Nobody is going to teach you your true history, teach you your true heroes if they know that that knowledge will help set you free.” In my opinion, the struggle we must embark on is the struggle to seek, affirm and unite.

The coalition that took place between black and brown marginalized communities in the film is representative of the coalition that is necessary to overcome oppression. The violence exhibited in response to the insidious nature of purging is symbolic for the intensity that we need to fight across all the spectrums of our life – in our politics, our education, our financial literacy, our core humanity. Americans, our survival depends on it.

Guest contributor, Monet Schultz, BU Class of 2018

Photo courtesy of Denise Jans, Unsplash photos

RIP Ntozake Shange

Author of For Colored Girls who considered suicide when the rainbow is enuf, who said:

“I write for young girls of color, for girls who don’t even exist yet, so that there is something there for them when they arrive.” — #NtozakeShange

Find Anne C. Bailey's non-fiction book :

Find Anne C. Bailey's non-fiction book :

Hello, this website is pleasant designed for me, since this moment i am reading this enormous informative post here

at my home. https://www.wmtips.com/tools/keyword-density-analyzer/?url=http://www.mbet88vn.com

I’m not that much of a internet reader to be honest but your sites

really nice, keep it up! I’ll go ahead and bookmark your website to come back later.

All the best http://likes.avanimisra.com/188bet420504

Very good reading. The plight of humanity should not be political but it is dependent on all of humanity and more so of our leaders. It is essential we all (young and old alike) vote to preserve our values. We have this great opportunity next Tuesday.

Good article. I will be going through a few of these issues as well.. https://tealfarmsketodiet.com/

I just like the valuable information you supply

in your articles. I will bookmark your blog and check once more right

here regularly. I’m relatively sure I’ll learn many new stuff right here!

Best of luck for the following! http://www.stiffuk.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=Scr888.group%2Flive-casino-games%2F2486-joker123

@Monet, nice piece. I watched this movie and actually have not seen the original. A friend pushed me to watch it thinking I would like it and I too had similar reactions to you about where I thought it would go. It surprised me as well. Especially the block party because the truth is most of us constructed as inherently violent are really not, naturally petty theft and some pranks happened and one dude who was cooked (which is believable) were around, but on the whole we defied their image of us. It was they who started the violence, as they always do!

Anyways, keep this writing up, you have always been a solid activist and advocate for Black liberation from Babylon the pieces like this are nice reading. One slight issue I had with the movie, and folks this is a spoiler so don’t read if you don’t want, is I took exception to the ending scene when they were escorting Dmitri out to receive medical attention and Dolores was telling people to make way as a King was coming through. I feel yes Dmitri was but what about the others? Dolores herself and Nya? Why can’t say Luisa’s and Dmitri be switched?

Or is there a way to not have Nya be burdened as all Black women are as a superwoman taking care of the house, family, and taking up the gun? Now this is realistic unfortunately, but idk why can’t we imagine something different? Back to centering Black men as the warriors protecting the family no? This doesn’t detract too much from the movie, but to me it does reproduce and old narrative we are currently trying to shake in our liberation struggle. Anyways, thanks for this blog post and thanks Dr. Bailey for opening the space to Monet, as you know, she is amazing!

Its like you learn my mind! You seem to know a lot approximately this,

such as you wrote the e-book in it or something. I believe that you simply could do with a few percent to drive the message home a little bit, but other than that, that is fantastic blog.

A great read. I will certainly be back.

Thanks so much for your support. Please keep reading and sharing the blog with others.