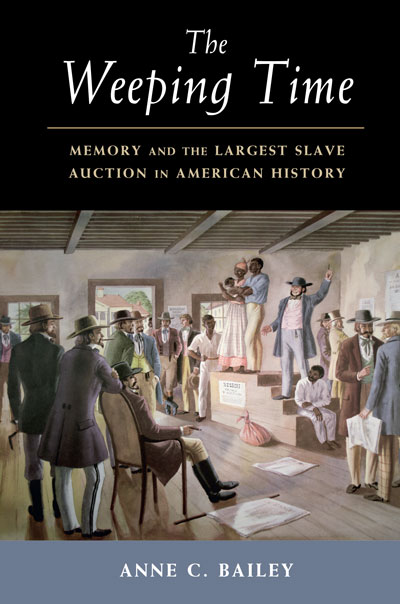

Two years ago, I wrote a book called The Weeping Time about the largest slave auction in American history. This experience which the enslaved called The Weeping Time took place in Savannah, Georgia on two fateful days, March 2-3 in 1859.

Today, we seem to be experiencing another Weeping Time—this time on a global scale.

Is there anything, I wonder, that the Weeping Time of yesterday can teach us about the Weeping Time of today?

To pull some hope out of this crisis, I look to my trade—my work as a historian and a writer to see if I may find answers, albeit partial answers.

The first thing that comes to mind is the trauma that forever changed and shaped the lives of the 436 men women and children, including 30 babies, on the auction block. Separation on the auction block was a kind of death, a social death. Even as late as 1859, there was no telling when the scourge of slavery would end, and in fact, the domestic slave trade between the Upper South and the Lower South, in part because of the ban on the international trade, soared in the decades before the Civil War. Slavery was one long night that, in spite of valiant efforts at resistance by Blacks and whites in the United States and across the pond in England, would not end without a fight. Indeed it took 620,000 lives in the American Civil War and continued efforts of resistance from abolitionists to ring the final death knell on the “peculiar institution.”

And so, there is this trauma, but there is also something else I found in the retelling of this story. Though those two days forever transformed the lives of the enslaved, their story did not end on the auction block. Their separation from their families and the only home they had ever known – the Butler Plantation estates of SE Georgia – was only part of their journey. Their lives as enslaved people in which they worked for others’ benefit were burdensome to be sure, but this African American community, part of the Gullah Geechee speaking community of Southern Georgia, then and now demonstrated a kind of resilience which may just help us get through these dark times.

The Civil war began two years after the auction event and several of the enslaved who had been sold escaped to the Union lines and volunteered for the war effort. They would fight for their freedom, but also fight for the freedom of all America. When the war was over, like so many other African Americans, they put family first. Many newly freed persons went looking for their loved ones, often on foot, placing ads in Black churches and newspapers around the country. Their cry was “Help me to find my people.” Some were fortunate and found one another, but others had few options but to settle down wherever they could. They married and built new families. Still others explored new opportunities for employment and education. And this they did without reparations since the brief and tentative offer of 40 acres and a mule was rescinded after Lincoln’s assassination in 1865. In spite of this, their many descendants in the present day, a number of whom I have had the privilege to interview, are a testimony to their resilience – to their determination not to let the auction block define them but instead to honor their ancestors by their survival and contribution.

Divided America

So it is a story of trauma and resilience but what else can this story teach us? Sadly, though some of those sold and almost 200,000 African Americans fought to unite America in the Civil War, America is again divided and nothing has put that in stark relief more than this coronavirus. Back then, the “owners” of the enslaved and the country as a whole did not acknowledge their dependence on them for unrequited profit; furthermore, save for a relative few, they did not see the inherent wrong with such inequities. Today, we struggle to acknowledge and to rectify these historical and contemporary inequities. Others have written more eloquently than I about how the virus has exposed the fissures in our society and other societies too. This, sadly, is not just an American problem. Those at the margins –the poor, the homeless, the undocumented, the prisoners, racial minorities—where are they in this crisis? How do they shelter in place at home? How will they get healthcare when they need it? Will some even feel comfortable coming forward to be counted in our modeling and statistics as is vitally necessary in a public health crisis?

Today I am seeing that the denial of interdependence is literally the difference between life and death. While this virus is revealing in a sad and powerful way the inequities in our society on the lower end of the spectrum, it is also revealing what is happening on the higher end. The uber wealthy can retreat to private yachts while others, particularly in urban centers, struggle to stay healthy in cramped yet expensive spaces. Likewise, access to testing is not the same for the poor as it is for the wealthy. The stories keep coming in of rich athletes, TV personalities, artists and others getting tested -even those who are asymptomatic—while some with symptoms, yet less wealthy and not so famous cannot get a test.

It must be said that this inequity is not the fault of our healthcare workers who are so bravely fighting for their lives and ours at this time. It is not even the fault of those celebrities who are making the most of their privilege to access good healthcare in a crisis (for who amongst us would not do exactly the same thing had we the opportunity?) The fault lies with a system which at times is eerily reminiscent of the era of slavery — a time in which some lives mattered more than others. Thanks to the sung and unsung heroes of the Abolition and Civil Rights movements, we have made improvements upon our foundation, but much more improvement is needed now and AFTER this Weeping Time.

A Vision

This divided America –this two-tier system—exposed by the virus is almost begging for a new vision: A 2020 vision to correct our blurred vision. After Corona, I would like to imagine a country and a world built on what Rev. Dr. Martin King Jr. called “agape love,” – defined as the highest form of love and charity, a selfless, unconditional love. If this virus does nothing else, let it call us to a time of radical love for one another and radical appreciation of our interdependence. It may be a dream, but as poet Langston Hughes famously said, “Hold fast to dreams, for if dreams die, life is a broken-winged bird that cannot fly.”

The King vision was always about others—not just African Americans or Black people, in general. It was always about all of America and the entire world. He saw the Black experience as an opportunity for the US to get things right—to provide a corrective to the gaps in The Constitution and The Declaration of Independence at the time of its founding. King felt that addressing the inequities of the Black experience would help America live up to the ideals of the Christian faith, but his appeal was not just to followers of the Christian faith, but to any and all who privileged love, compassion, and equity.

In the spirit of Thomas Jefferson’s groundbreaking Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, based on the principle of the separation of church and state, King’s vision resonated with the notion of being our brother’s keeper regardless of our diverse religious expressions or lack thereof. King did not have a litmus test of faith for his followers or for those who marched alongside him. He marched with people of diverse faiths- Catholics, Protestants, Jews and others – and he marched with atheists. What they all bought into was this notion of agape love.

It is that vision…that I would like to resurrect today for our times, for good times, for Weeping Times, for a time such as this.

So as I think about many who have lost loved ones in this current moment, including myself, and the state of affairs right now, I wish I could offer more. If I were rich, I would purchase Personal Protective Equipment (PPEs) for our healthcare workers. If I were a political powerbroker, I would ensure that when an appropriate vaccine is discovered, (because it will be), every person in the world regardless of income, race or color, would have access to it. If I could sing, I would sing songs of comfort and even humor to lighten the load like some of our artists. If I were a healthcare worker, I would administer care as many are so bravely doing; If I were a first responder (EMS, ambulance, fire or police) I would protect and serve. But I am only a writer, and sometimes I think all I can do is write a vision and make it plain as a healing balm as much for myself as for others, and hope that kernels of my partial answers may help bring us out of this dark night.

“Weeping may endure for a night, but JOY comes in the morning.” Psalm 50

Come morning, come.

By Anne C. Bailey

Edited by Bernice deGannes Scott Ph.D.

Photo by Frank McKenna on Unsplash.com

This article is dedicated to my sister, Valda Alicia “Meg” Bailey, an American citizen originally from Jamaica, mother of seven and much loved by her family and friends. She died on March 30 in Brooklyn, New York.

Find Anne C. Bailey's non-fiction book :

Find Anne C. Bailey's non-fiction book :

Such well written piece of history or will become part of our history. Not because it’s coming from my aunt but it’s coming from a prolific writer of our times. Keep writing aunty we’ll appreciated.

Beautiful, Anne. Thank you.