In recent days, some citizens in our midst have called for others to “be sent back to where they came from.” I am thankful that those who repeated such a disturbing chant do not represent all of us but for any who are convinced this was just an idle chant, like the rant of a cranky uncle at Thanksgiving, (who doesn’t have one?), let me tell you a story or rather retell you a story. It is the story of members of the Caribbean Windrush generation who as British citizens made their lives in Britain and in 2013 due to a new anti-immigration “hostile environment” policy were wrongly classified as illegal immigrants, and not just told to go “home,” but were sent there. Talk can easily translate into action …under the right circumstances. So for those of us who dismiss this talk and think that our silence will make it go away, I hope that the story below inspires you to speak up. Let your voice be heard in any way that you choose. It is your choice but know that in this one situation alone, thousands of lives were disrupted and some even lost due to this sudden change in policy. Even now, with apologies and reparations on the table, it is the kind of harm that can’t be completely undone. These people have been through a trauma that rectifying their papers and compensation can not alone undo.

Dear readers, I hope you will voice your views. When the rest of us are silent, we become sadly complicit. Let the world know that those who chant this way do NOT represent this special place called America; that they can not destroy this sometimes fragile fabric of many cultures and nations within ONE nation; that we can not and should not esteem some lives more important than others. This is not a Republican or a Democratic issue. Everyone has the right to belong to the party of their choosing. Every American has the right to his/her point of view on any particular issue but a difference of opinion or one’s ancestry should not change one’s legal status.

In the Windrush case, some have thankfully let their voices be heard. The amazing reporters at The Guardian were the first to break the Windrush story and writers and activists like Emma Lewis, Professor Bernard Headley and University of West Indies Senior Lecturer, Dr. Hilary Robertson Hickling have not let this story die. How very pertinent it is to us today!

The Caribbean Windrush Generation, Colonialism and the Idea of Home

(originally published May 2018)

I am an American citizen but I was born in Jamaica, a former colony of Great Britain. When I was growing up, I did not really understand what that meant. I knew only that we spoke English and Jamaican patois but English was the official language. I knew too that we learned a lot about British history in and out of school. I knew we celebrated British holidays like Boxing Day – the day I was born. Boxing day is the day after Christmas which was traditionally celebrated like a second Christmas day, particularly for household staff in England who had to work on Christmas Day.

Growing up in Jamaica, I had no knowledge of the specifics of this history and I suspect it was the same for many around me. We just knew that Boxing day was a holiday and it meant additional time with family since all places of business were closed. In fact, many of us enjoyed a day at the beach on Boxing Day. These things were just traditional and they spoke to us of home. Likewise, we ate elaborately decorated buns at Easter and rich wine soaked fruit cake at Christmas—again because that is what the British used to do and that is the legacy they left; that is the legacy we kept. That too spoke to us of home.

So when hundreds of Caribbean residents embarked the MV Empire Windrush on May 28 1948, they got on that ship as British subjects—as knowledgeable about Britain as anyone who lived in the “mother country.” Some of them had even fought alongside Britons in World War II. Certainly, they had literally learned more about Britain than they had about Jamaica or Africa or anywhere else for that matter. Noted African author, Ngugi wa Thiong’o in his memoir, In the House of the Interpreter, writes eloquently about that phenomenon. As another person with a British colonial legacy, in his case, Kenya, he wrote about going to an elite school called Alliance where he learned much about Britain but very little about his place of birth.

And so for these and other reasons, Britain was not an unfamiliar place for these African descended Jamaicans and other Caribbean peoples. They were not strangers. So much of their lives had been influenced by England that it might only have been the weather that was unfamiliar.

But they forged on. They built a life there and called Britain home in a new way. They became nurses, bus drivers, railroad engineers. Others laid railroad tracks, and still others took care of the elderly. They bought homes, had families and settled down. Yet now, since a new policy was put in place in 2013, this Windrush generation, many of whom are now seniors, have been asked to leave. They have been asked to pack their bags and find another home because Britain –the Britain that they helped to rebuild after the ravages of war – is no longer to be their home.

Reportedly, this situation is now to be resolved but when? And what about those who are already in Barbados and Jamaica in a kind of no man’s land of citizenship? Will their situation also be sorted out? Will they be able to come back to Britain as citizens if they choose or go back and forth as they please?

Who will compensate them not only financially but emotionally for that sense of being ripped from their home because of new and more pressing political agendas? Even if and when all is rectified, will they ever feel again like they are truly home? To be clear, up until recently, for a number of Caribbean descended nationals, returning to the Caribbean was a goal — but it was their choice to return to the Caribbean, not because they were being deported.

These are the questions I am asking as I think about the idea of home and what the legacy of colonialism really means; how that legacy disrupts ideas of home in the past and as it turns out, also in the present.

But the good news is that it is not too late to make things right. The British Home Secretary apologized and promised on March 30 that the policy would be overturned and that amends would be made in two weeks. I was very glad to hear about this commitment and hope that indeed all benefits of citizenship will be restored to every one of these British citizens. As of this writing, many are still waiting for the promised change. I remain hopeful, however, that the office of the British Home Secretary will honor their word.

A little universal thing called home. It truly matters. May Britain in this new era also remember its history, and in so doing, set an example for the world.

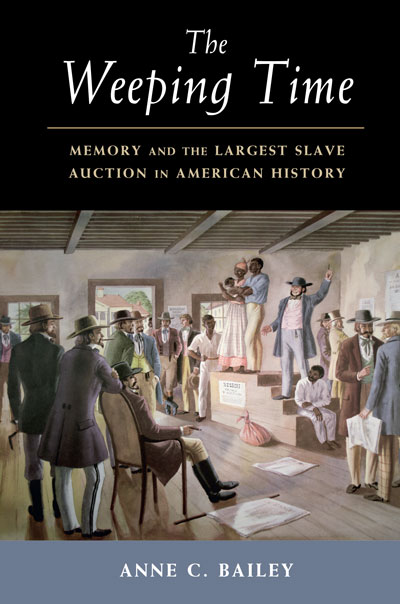

Anne C. Bailey, Author of The Weeping Time: Memory and the Largest Slave Auction in American History (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

Windrush Square, Brixton The SS Empire Windrush brought the first generation of migrant workers from the Caribbean to England in 1948, many of whom settled around Brixton, London.

Attribution: Danny Robinson [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)]

Find Anne C. Bailey's non-fiction book :

Find Anne C. Bailey's non-fiction book :